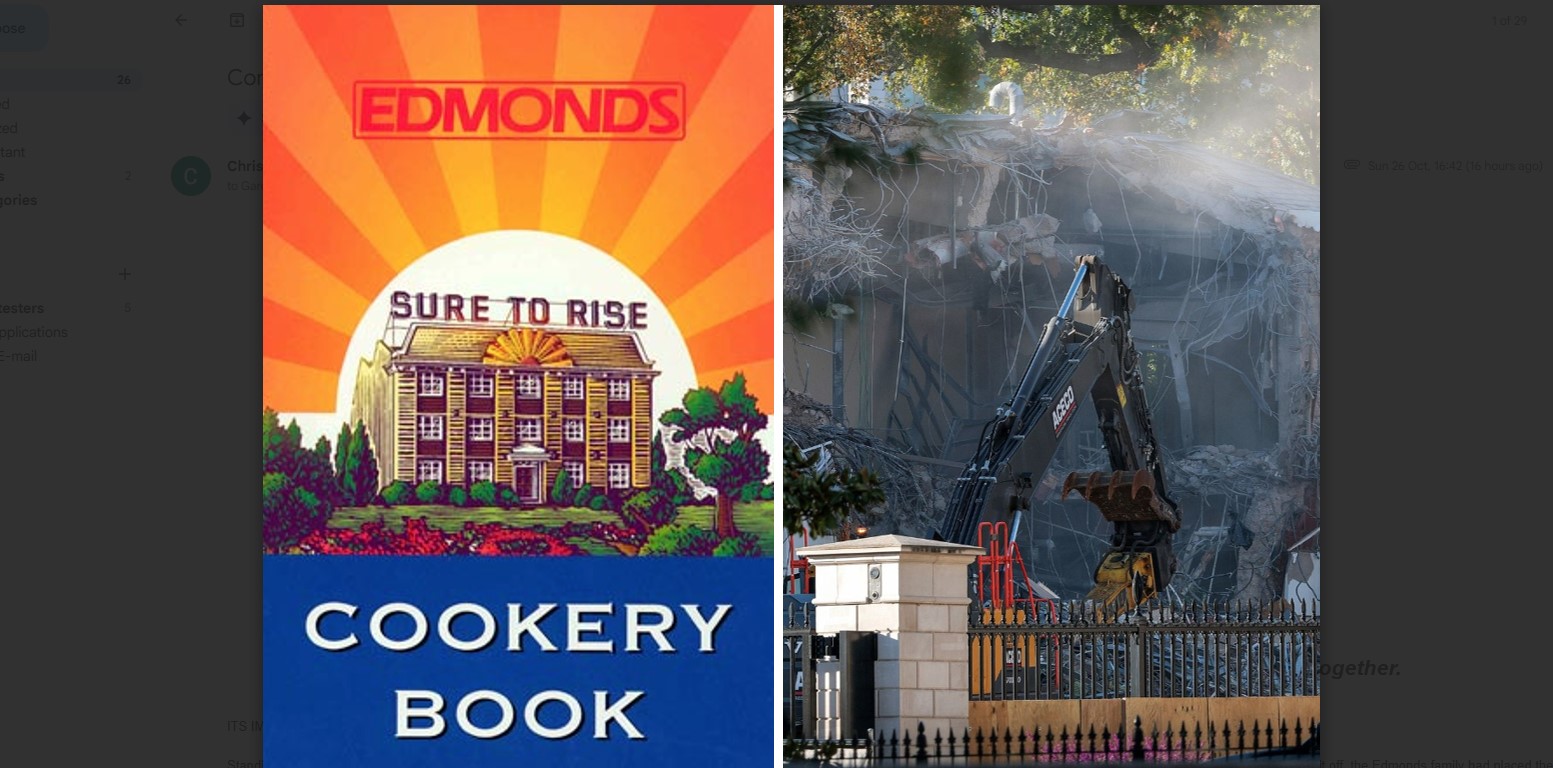

Its image graced a national bestseller. Indeed, the Edmonds family’s Christchurch factory could lay credible claim to being one of New Zealand’s most iconic buildings.

Standing amidst lovingly maintained gardens in the midst of Woolston’s industrial sprawl, the factory’s façade was an architectural oddity – as if a cottage had taken too many steroids. To top it off, the Edmonds family had placed their company’s slogan on the façade’s roof in letters three metres high.

“Sure to rise” was a reference to the company’s baking powder but, over time, New Zealanders would invest it with meanings of their own.

How does a building become iconic? Truthfully, the answer has very little to do with architecture. A building becomes iconic by virtue of being seen. It was the family’s decision to put the façade of its Woolston factory on the cover of the Edmonds Cookery Book – a publication whose 4 million sales meant that it could be found in just about every New Zealand kitchen – that transformed the building into a national icon.

It is, therefore, entirely understandable that when the building was demolished New Zealanders were crushed. No amount of submitting, or protesting, or last-minute appeals, made the slightest difference.

Edmonds had fallen victim to the quintessential corporate raider, Ron Brierly, in the 1980s. The century-old family company was very far from being the first to be asset-stripped and reduced to rubble, but the unique place it occupied in the national imagination meant that its destruction could not avoid making headlines.

Also unavoidable was the way in which the building (bowled-over and its gardens bulldozed flat in a matter of hours as local residents scrambled to rescue what they could of its contents) came to symbolise the way pre-1984 New Zealand had been flattened to make way for Roger Douglas’s free-market future. When those three-metre-high letters came crashing to the ground in 1990, everybody understood that “old” New Zealand would not rise again.

What stirred these thirty-five-year-old memories? It was the ruthless destruction of another iconic building – the East-wing of the White House in Washington DC. Somehow, heavy demolition equipment had made its way onto President’s Park – a supposedly federally-controlled National Park – and in a matter of hours reduced this 1942 addition to the White House complex to a pile of rubble.

Now, bowling-over an edifice that had stood beside the Executive Residence for a mere 83 years may not seem all that important. After all, the White House (so called for the white coat of paint applied to mask the extensive charring caused by British soldiers during the War of 1812, is an impressive 233 years old.

But that, surely, is the point. Every president since George Washington’s immediate successor, John Adams, has occupied the Executive Residence for the duration of his presidency. It has become an integral aspect of the office of president – alongside the Oath of Office and the Inaugural Address. So much so that the words themselves, “the White House”, have achieved synecdochical status. When a journalist declares “the White House said today”, they are referencing the president and his staff.