President Roosevelt’s introduction of United Nations Day and his Four Freedoms boosted morale in the fight against fascism and set the stage for a post-war UN.

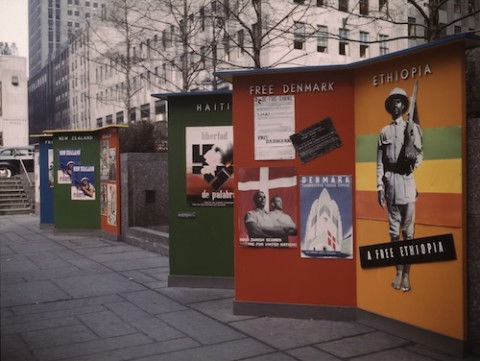

14 June 1942 was the first United Nations Day. An event launched by US President Franklin Roosevelt six months after the United Nations was established on New Year’s Day that year, it was celebrated around the world. Nowadays, UN Day is October 24th (marking the formal ratification of the UN in October 1945). The connection between the United Nations and the Second World War has almost entirely been forgotten, and the date is more likely to be remembered as the day that Anne Frank began her diary. If it is marked at all, it is as a non-governmental occasion at the fringes of national life. But between the first United Nations Day in June 1942 and spring 1945 (the time of the creation of the UN Charter at San Francisco), the United Nations became a political-military alliance without which the outcome of the Second World War would have been different and the UN we know today non-existent. During this period, United Nations Day played an important part in the international political mobilisation for the war and the peace that followed.

In the spring of 1942, with the Japanese threatening to repeat Pearl Harbor and bomb targets on America’s West Coast, and with U-boats sinking ships in sight of Long Island, Roosevelt needed to boost morale. In the 1930s, he had used parades as a means of getting across the idea that his New Deal was getting people back to work. He used a similar approach on a global scale in the Second World War. The rousing of martial spirit was underpinned by the ideals Roosevelt had espoused first in his Four Freedoms speech of January 1941 and then in the eight-point Atlantic Charter of war aims issued with Churchill that August. These points included social security and labour rights alongside free speech and self-government.

The nationwide programme centred on a declaration of principles governing national policies drawn up between Churchill and Roosevelt and set out in the United Nations Declaration of January 1942. It was planned to lead up to a national observance on 14 June 1942, which a presidential proclamation set aside as United Nations Day. Clubs, churches, unions and other organisations were urged to devote one of their monthly meetings in either May or June to the United Nations’ role in winning the war and the Atlantic Charter’s in the ensuing peace. Radio broadcasts on the subject were transmitted, and simultaneous mass meetings were to take place nationwide on June 13th. The president outlined his vision in a letter to Clark M. Eichelberger, Chairman of the United Nations Committee:

Nothing could be more important than that people in the United States and of the world should fully realize the magnitude of the united effort required for this fight ... I have read with interest of your plan to inform our people of the United Nations’aspect of the struggle ... With the vital contribution toward winning the war that has been made, is being made, and will be made, by each of our allies, we shall be successful in our struggle against Axis domination of the world by force of arms.

Many supported the president’s rallying cry. Archibald MacLeish, Director of the War Department’s Office of Facts and Figures, stated:

It is naturally of the utmost importance that all the people of these nations engaged in the struggle against slavery shall understand each other to the greatest possible extent. To that end, it is desirable that as many civic organizations and other bodies as possible, will, during May and June of this year and also during months that follow, stage celebrations which will heighten the understanding among the United Nations.

The response to Roosevelt’s initiative was huge, both nationally and internationally. From Culman, Alabama, to Stoke-on-Trent in England and the Kremlin in Moscow, UN Day provided a focus of solidarity. Sigrid Arne, the pioneering female diplomatic correspondent of Associated Press, reported how ‘Six months after the United Nations were formally allied through the Declaration, there was a world celebration to dramatise the union. The notion of the United Nations was taking hold’.

In April 1942, Lord Halifax, the British Ambassador to Washington, had telegraphed London to outline the President’s strategy:

The Administration is seeking ways and means of bringing home to American people the existence of the United Nations of which this nation is but a part, and it is in our interest that such a campaign should succeed, for with the exclusion of China, Australia and perhaps Russia we and other nations are apt to be left in the background and even our successes are often attributed in the press to the assistance which we obtain from American participation. It is reliably stated that the President is considering announcing the fact that June 14th normally celebration as Flag Day and is seeking the involvement of the British other allies.